|

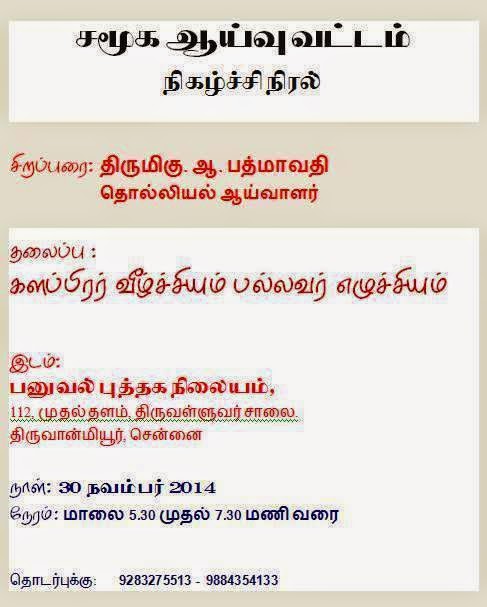

| Dr. S. Chandnibi of Aligarh Muslim University.

|

|

| Epigraphical Reading in the Chola History |

|

|

| The nine foot

tall stucco statue of Nandi installed on a twelve foot pedestal about

four hundred years ago stands out majestically on the baked |

Think history, think of the Mauryas, the Guptas, the Sultanate and the

Mughals. Maybe, somewhere down the line sneak in a chapter on the

Cholas, and a paragraph or two on the likes of the Pandeyas, the Cheras,

the Vakatakas and the rest. Some though have gone beyond this lopsided

approach to our history and focussed on the achievements of the Cholas,

the empire that lasted more than a millennium. Many years ago, the

venerable Nilakant Sastri came up with a landmark study of the Cholas.

Recently, S. Chandnibi, an academic at Aligarh Muslim University,

concentrated on epigraphical data from the dynasty in her book,

“Epigraphical Reading in the Chola History” to reveal to us some of the

evidence of the vastness of the empire.

Beyond Nilakant Sastri, not many top historians seem to have focussed

exclusively on the Cholas. Your book fills that vacuum. How challenging

was it to do a book on the Cholas that goes beyond academic circles?

I dare not to be placed anywhere near K.A. Nilakanta Sastri. He a giant,

never left a stone unturned in the field of Cholas, which itself is too

big a challenge for anyone to progress further. Next handicap is the

sources, where we should look to epigraphy only, as we lack literary

sources as compared to contemporary north India. Among the painstakingly

copied inscriptions, ASI has published little, and also the efforts of

the State government are too little when compared to other neighbouring

States. So one has to wait for permission

The Cholas were renowned for local self-administration. Were they the harbingers of local self government in modern India?

We may say so. The ancient north Indian literature refers to republican

States and two different houses of the State, viz Sabha and Samithi, and

we hardly see its practicality here. But Sabha and its full fledged

functions are quite obvious in the regime of the Cholas. In certain

issues —irrespective of the difficulties of matching with the exact

perspectives of present-day democracy — definitely we are yet to catch

up with the Chola system, especially in dealing with corruption in

general and politicians in particular. The most amazing aspect was their

effort to maintain zero tolerance towards public corruption. Public

money swindlers were debarred from contesting the elections for life.

Could you elaborate on the Cholas’ justice system?

It was more practical in a certain sense, like when two brothers fought

with each other and one was murdered, the other was exempted from

imprisonment taking into account the aged parents left with no other

sons; he was left free with a caution to guard his parents. The

caste-based justice of Manu did not find routes with the Cholas’

justice. At the village level grievances were dissolved by discussion,

unmindful of whether it was day or night. Traditions were given

importance but overcome if documental evidence was produced. The various

stages of the present system, right from filing a case to the final

judgement including the right to appeal, was followed in the Chola

judiciary. The king’s court was the only court of appeal. Even the

Brahmins were not spared; they were imprisoned, fined, had their

property confiscated and were deprived of their professional duties in

the temples for generations. Special care was taken to collect the

swindled public money. We do not hear about hard punishments like

thrashing, being trampled under elephants and amputation. An example is

the case of the murder of a prince by a group of Brahmins; the royal

authority did not execute them but confiscated all their and their

relatives’ property. At the same time, a very little parallel to Manu’s

influence could also be felt.

As youngsters we learn about Mauryan Emperor Ashoka’s expedition to

Sri Lanka as also the Battle of Kalinga. Yet we are told little about

how Raja Raja Chola I’s empire included Sri Lanka as well as Kalinga.

How do you explain this dichotomy?

This particular question may open a Pandora’s box. The historians of

north India really far exceed in the subject while the south is not yet

close to them. Eventually these developments led to a mental picture

that the history of north of the Vindayas is the history of the country

itself. The historical writings undermined the south and used a blanket

term “Indian” — though neglecting the southern touch. I can list at

least 50 such books, from my very department’s library . The chapter

“Feudalism in South Indian Context” of my book is self-explanatory in

this context. Though scholars the world over accept that the so-called

undeciphered Harappan script has links to languages of the Dravidian

family, we prefer to leave it aside as undeciphered. Though the familiar

division of Indian society into four on caste basis has been checked

and opposed right from its initiation in the Vedic age, still the basic

text books do not show this. All this implies the need for rewriting our

history books with absolute objectivity. A senior historian has voiced

long back that Indian history should start from the banks of river

Kaveri instead of the Ganga.

On similar lines our students are told about southern kings in one

single chapter, in which the Cholas, Pandeyas, Cheras are all clubbed

together despite the fact that often Cheras, Sinhalas as also the

Pandeyas allied against the Cholas. Doesn’t this short shrift to an

important Indian dynasty deprive our students of a more balanced

representation of our past?

Of course, there is no other dynasty in the whole of Indian history,

perhaps the universe, that has survived and continued to rule right from

B.C to the 13th A.D — which includes the complete ancient period and

partially the medieval one, with ups and downs, except the three, viz

the Cheras, Cholas and Pandeyas. The Greek and Roman writers exhibit a

sense of fear over the gold drain into these kingdoms caused by the

excessive imports in the Augustus Era. The two epics of India, Ramayana

and Mahabharata, do refer to them. Some of the tribes in the South East

Asian islands go with the names of the three dynasties. Asokan

inscriptions refer to them as neighbours, meaning they were independent

of the Mauryan yoke. Kharavela of Kalinga perceived the confederation of

these three dynasties as a threat. Even in Pakistan, Afghanistan and

the land beyond carry these dynastical names as their place names today

too. The Cholas were the first to excel in a navy and succeeded in

subduing the Far East islands politically, culturally and commercially.

Until the advent of the Europeans in sea commerce, the southern powers

had both east and west overseas commerce in their hands. Embassies were

sent to China as an extension of commerce. The dialogue can go on.

Yes, our younger generations are deprived of a marvellous piece of their history, which is definitely very unfortunate.

The Hindu November 28, 2014